Translation ︎︎︎ Self

This writing layors out the transitions of my identity, from tomboy, bu-fen to queer, and how they relate to Taiwanese history, my family hood, and self creation. This series are also part of Asterisk as a life form.

01 Tomboy ︎︎︎

This writing layors out the transitions of my identity, from tomboy, bu-fen to queer, and how they relate to Taiwanese history, my family hood, and self creation. This series are also part of Asterisk as a life form.

01 Tomboy ︎︎︎

In Mandarin, masculine and feminine genders1 appear in many different ways; most of the mandarin script is comprised of pictographic characters called radicals, such as in the case of the pronouns 他 ‘he’ and 她 ‘she,’ both pronounced [ta] but with different radicals, 亻indicates male, and 女 means female. When I was a kid, there was a limited vocabulary for communities outside of the gender binary, and the prior generation, before 1990, referred to queers and trans people as “nà gè“(那個) in mandarin, which means “that” in English. Language structure extends to our everydayness, and Taiwanese society has long been in aphasia and ignores human existence outside of the heteronormative social order.

In the 1950s, before the term “T,” indicating “tomboy,” was imported, the industrial economy just began to bloom in Taiwan. The stereotypes of gender and the expectation of monogamy is rooted in society’s values. When it comes to the women who dress in a neutral style and always wear suits, the public calls them “chuan ku de,” which means (women)in-pants in the Taiwanese language. In 1960s Taipei, these “chuan ku des” gathered through mutual friends and formed gangs2. Based on the preceding research, these gangs used to control theaters and red-light districts in Taipei.

From 1951 to 1971, due to the escalated clashes between China and Taiwan and the American military’s defense strategy in the western Pacific, thousands of American personnel and their families moved to stations in cities in Taiwan, bringing along consumerism and entertainment culture from the U.S. The term “tomboy” was imported with the openings of gay bars and clubs. Besides, from 1949 to 1987, due to the loss of the Chinese Civil War, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) imposed martial law. During this period of martial law, there were no political parties, human rights, or free speech; the KMT government controlled people’s thinking and reading and there was no freedom of expression. At that time, sexual minority communities were stigmatized and stuck with the narrative “the soul in the wrong body” and “they need to be saved” throughout the newspapers of 1980s Taiwan. People outside the gender binary turned to find and gather in specific spaces where they could hide and connect. These leisure and private spaces became their center of meaning3.

I first heard about the term “T” (踢) from one of my seniors, and she described me as“a baby tomboy” during high school4. In contrast to T, people call femme lesbians “Po” (婆) which means wife in mandarin. During my first two years in college, I experienced the night culture in Taipei in T-ba (bars for tomboys) and La-ba (bars more targeted at femme communities). However, I felt uncomfortable in the T-P structure, which to some extent, is still copying the structure and love roles of heteronormative relationships. At that time, I found no standpoint and value in gender identity and shifted from T to Bu-fen, which means “anti-categorize” in Mandarin. The non-binary turn in my identity was inseparable from changes in communication technologies and my living space. I first encountered the term “bu-fen” on HER, a dating app designed for the lesbian community. Similar to other dating apps, HER works by first setting up the account, browsing by swiping to match, and beginning to chat after the match. Here, the user interface becomes the space for identity discourse; by choosing your gender identity, daily interest, and ideal types, the algorithm arranges many matched users in images.

In the 1950s, before the term “T,” indicating “tomboy,” was imported, the industrial economy just began to bloom in Taiwan. The stereotypes of gender and the expectation of monogamy is rooted in society’s values. When it comes to the women who dress in a neutral style and always wear suits, the public calls them “chuan ku de,” which means (women)in-pants in the Taiwanese language. In 1960s Taipei, these “chuan ku des” gathered through mutual friends and formed gangs2. Based on the preceding research, these gangs used to control theaters and red-light districts in Taipei.

From 1951 to 1971, due to the escalated clashes between China and Taiwan and the American military’s defense strategy in the western Pacific, thousands of American personnel and their families moved to stations in cities in Taiwan, bringing along consumerism and entertainment culture from the U.S. The term “tomboy” was imported with the openings of gay bars and clubs. Besides, from 1949 to 1987, due to the loss of the Chinese Civil War, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) imposed martial law. During this period of martial law, there were no political parties, human rights, or free speech; the KMT government controlled people’s thinking and reading and there was no freedom of expression. At that time, sexual minority communities were stigmatized and stuck with the narrative “the soul in the wrong body” and “they need to be saved” throughout the newspapers of 1980s Taiwan. People outside the gender binary turned to find and gather in specific spaces where they could hide and connect. These leisure and private spaces became their center of meaning3.

Micmicking peeing like a boy in high school

I first heard about the term “T” (踢) from one of my seniors, and she described me as“a baby tomboy” during high school4. In contrast to T, people call femme lesbians “Po” (婆) which means wife in mandarin. During my first two years in college, I experienced the night culture in Taipei in T-ba (bars for tomboys) and La-ba (bars more targeted at femme communities). However, I felt uncomfortable in the T-P structure, which to some extent, is still copying the structure and love roles of heteronormative relationships. At that time, I found no standpoint and value in gender identity and shifted from T to Bu-fen, which means “anti-categorize” in Mandarin. The non-binary turn in my identity was inseparable from changes in communication technologies and my living space. I first encountered the term “bu-fen” on HER, a dating app designed for the lesbian community. Similar to other dating apps, HER works by first setting up the account, browsing by swiping to match, and beginning to chat after the match. Here, the user interface becomes the space for identity discourse; by choosing your gender identity, daily interest, and ideal types, the algorithm arranges many matched users in images.

1. Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge, 1989.

2. Some of the gangs also include gay man as a sister (jié bài xiōng dì). See more: Huang, M. Suits and Corsages: Taiwanese Women in Pants During the Early Post-War Period (thesis), 2018.

3. The evolution of pronouns for transgender is inseparable with two aspects; on one hand, gender dysphoria (GD), a medical terms refers to psychological distress that results from an incongruence between one’s sex assigned at birth and one’s gender identity; on the other hand, the discourse of transgender subjectivity as an umbrella term proposed by Taiwanese feminist scholar, Josephine Ho. In her lecture in Tokyo in 2003, she claimed that “not as any dependent group of subject distinct from gays, lesbian and other minor sexualities, instead, transgender could be used as a term that describe the many diversity of gender variance and gender ambiguity that we see among varied population.” The development of medical diagnosis and Ho's discourse weaves together and lays the foundation of narratives and politics of Taiwanese transgender. See also Liu, Y. T., Mapping of Transgender : Shaping of "Transgender'' Identity in the History of Taiwan's Gender Movement. 2022.

4. During high school, I had gone through a renewal, furthermore an enlightenment from my high school teacher. In high school, every week students are asked to exchange the weekly diary with our teacher. In the weekly diary, I opened up my concerns and lost my identity. I always remember when I’m writing about my come-out: “What if they don’t understand or recognize the real me? So what?” In the next day, I received the diary and saw she underlined the sentence with her red marker, and written that “never lose the true you, and it’s critical to understand yourself.”

2. Some of the gangs also include gay man as a sister (jié bài xiōng dì). See more: Huang, M. Suits and Corsages: Taiwanese Women in Pants During the Early Post-War Period (thesis), 2018.

3. The evolution of pronouns for transgender is inseparable with two aspects; on one hand, gender dysphoria (GD), a medical terms refers to psychological distress that results from an incongruence between one’s sex assigned at birth and one’s gender identity; on the other hand, the discourse of transgender subjectivity as an umbrella term proposed by Taiwanese feminist scholar, Josephine Ho. In her lecture in Tokyo in 2003, she claimed that “not as any dependent group of subject distinct from gays, lesbian and other minor sexualities, instead, transgender could be used as a term that describe the many diversity of gender variance and gender ambiguity that we see among varied population.” The development of medical diagnosis and Ho's discourse weaves together and lays the foundation of narratives and politics of Taiwanese transgender. See also Liu, Y. T., Mapping of Transgender : Shaping of "Transgender'' Identity in the History of Taiwan's Gender Movement. 2022.

4. During high school, I had gone through a renewal, furthermore an enlightenment from my high school teacher. In high school, every week students are asked to exchange the weekly diary with our teacher. In the weekly diary, I opened up my concerns and lost my identity. I always remember when I’m writing about my come-out: “What if they don’t understand or recognize the real me? So what?” In the next day, I received the diary and saw she underlined the sentence with her red marker, and written that “never lose the true you, and it’s critical to understand yourself.”

02 ︎︎︎ Bu-fen

The term, Bu-fen, originated from a lesbian book club with a feminist background in 1990s Taiwan. After the White Terror Era ended in 1987, the rephrasing of terms for gay/lesbian/queer community started to appear with the importing and translation of the works of western queer studies and theorists. Democratization in 1987 allowed more rethinking of gender and sexuality to take place, for example, lesbian and (more broadly) queer activists started allying with feminist movements to obtain more support for their cause. From 1990 to 1995, lesbian and gay social and activist groups across campuses and in the public forum began to form social clubs and alliances, including Between Us and Gay Chat, a gay student society at National Taiwan University. In the era of globalization, facing the rooted constraints of traditional structures, many lesbian and gay activists endured a hard time taking root and coming out. Activism and social movements became their collective appearance. Whereas in the west, movements for feminism and cultural diversity preceded the struggle for LGBTQ+ inclusion, in Taiwan, all three things happened simultaneously.

“The past may not be the present, but it is sometimes in the present, haunting, even if only through our uncertain knowledge of it, our hopes of surviving and living well.” (Carla Freccero, 2008) Though I’ve found comfort in bu-fen, the narrative, “soul in the wrong body” from the 1980s society still haunts the present, through kinship and Taoism.

My mom met Master Han, a Taoist priest, in her mid-20s through a friend’s connection. Since then, when making big decisions, from choosing a husband to medical decisions, my mom will turn to Master Han for suggestions. “Master Han has saved many lives, including mine, my dad’s, and your grandpa’s.” In the early years, Han claimed that his mission was to deliver the message from Han Xiangzi, one of the legendary xian (“immortals”) in Taoism mythology, and to bring peaceful life to believers. After my sister and I were born, every year my mom would bring us to the temple at Kaohsiung for blessings and signs6.

From my perspective, Master Han is my mom’s therapist, who offers comfort and peacefulness from Taoism mixed with Confucianism. However, in his narrative, my sexuality is a phase that will eventually “return” to a heterosexual family, and to “quicken” the process, he suggested (through my mom) to swear with Lan Caihe5, also one of the legendary xian, whose gender is ambiguous.

The identity gets entangled with the temporality of others; through moving to different narratives and centers of meaning, I became an object first interpreted by the image, the character, and the discipline in their religion. Secondly, identity is also tied with the family, which affects my perspective of self at the same time. In humanistic geography7, the center of meaning is tied with collective experiences of territory, religion, economics, and politics. Here, the generational gap between my mom and I regarding life and identity, collapses unequally into each others’ centers of meaning. The interpretation of gender and sexuality in Master Han’s temple, becomes a form of territorialization and deterritorialization, through the power arrangement in kinship, gendered social value, and religion.

5. A woodblock print of Lan Caihe as a young person wearing long robes and carrying a flower basket. Originally printed in the Huan Chu version of the Liexian Zhuan, c. 1206–1368 CE, reproduced 1916 CE.

5. A woodblock print of Lan Caihe as a young person wearing long robes and carrying a flower basket. Originally printed in the Huan Chu version of the Liexian Zhuan, c. 1206–1368 CE, reproduced 1916 CE. 6. The process of seeing master Han is simple: first, text the master’s wife through the LINE app, and set up the appointment for the upcoming weeks. Second, my family and I will drive for 1 hour to the temple in Kaohsiung. After arriving, we’ll light up the incense sticks for each of us and worship Jade Emperor (thin-kong-lô) before its censor. After sticking the sticks, we’ll enter the temple and pick up the pink papers to write down your question and related keywords(name, place, etc.), then wait until it’s our turn to meet the master. Master Han used to advise us for the future, but recently his method changed to giving yearly blessings.

7. Tuan, Y.-F. (1976). Humanistic Geography. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 66(2), 266–276. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2562469

03 ︎︎︎*

My drawings and the process of creating zines became a way to break out. In 2019, I collected my drawings into a zine and set up my drawing account on Instagram. I also attended art book fairs around Taiwan with my friends and met more communities from different subcultures. Zines8, as creations of self, become the bridge between my personhood and readers9, and even go beyond identity politics through reading and flipping books together.

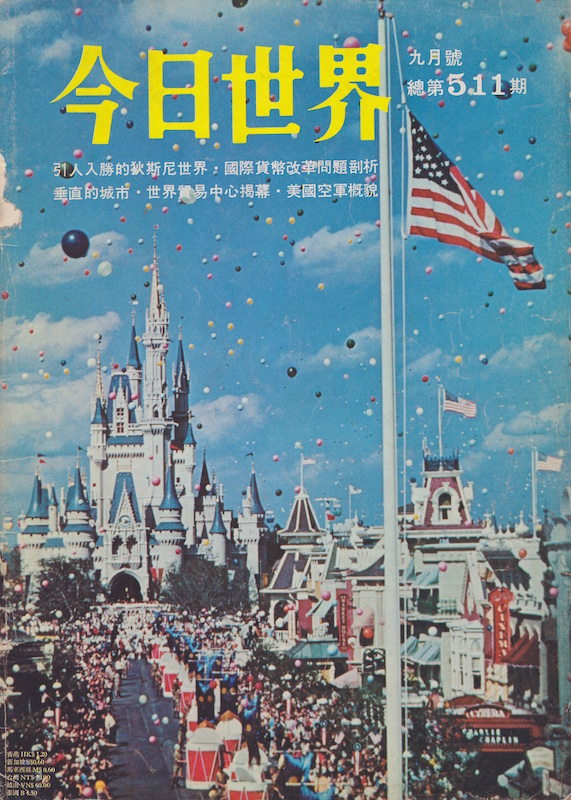

In Taiwan, the term “zine” was introduced around 2010 and translated as “siaǒ jhìh”(小誌), means little-magazine in mandarin. At that time, independent and DIY publications gained increasing popularity and attention in the cultural and academic fields. The practice of zine-making started after lifting martial law in 1987, and the developments of Tangwai’s press (means outside-of-KMT party) and little magazines from the 1970s to the 1980s are significant precursors to Taiwanese zine culture. The Lend-Lease Act launched by the U.S. in 1941, authorized military, economic, and technical aid to Taiwan. Beside importing material and consumerism culture, the U.S. also established the USIS (United States Information Service) in Taipei as a cultural and diplomatic station in charge of spreading global news and U.S. politics, introducing art exhibitions, and translating western literature. From 1949 to 1980, USIS published its magazine World Today, printed in Hong Kong, and mainly focused on global politics analysis, literature, and entertainment. Under the Cold War and the closed social climate, World Today magazine10 not only played as the central informative resource for Taiwanese elites and artists but also the exposure platform for writers in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the United States, which became viral among young readers in the 60s and 70s.

In Taiwan, the term “zine” was introduced around 2010 and translated as “siaǒ jhìh”(小誌), means little-magazine in mandarin. At that time, independent and DIY publications gained increasing popularity and attention in the cultural and academic fields. The practice of zine-making started after lifting martial law in 1987, and the developments of Tangwai’s press (means outside-of-KMT party) and little magazines from the 1970s to the 1980s are significant precursors to Taiwanese zine culture. The Lend-Lease Act launched by the U.S. in 1941, authorized military, economic, and technical aid to Taiwan. Beside importing material and consumerism culture, the U.S. also established the USIS (United States Information Service) in Taipei as a cultural and diplomatic station in charge of spreading global news and U.S. politics, introducing art exhibitions, and translating western literature. From 1949 to 1980, USIS published its magazine World Today, printed in Hong Kong, and mainly focused on global politics analysis, literature, and entertainment. Under the Cold War and the closed social climate, World Today magazine10 not only played as the central informative resource for Taiwanese elites and artists but also the exposure platform for writers in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the United States, which became viral among young readers in the 60s and 70s.

8. My second zine, Mirror

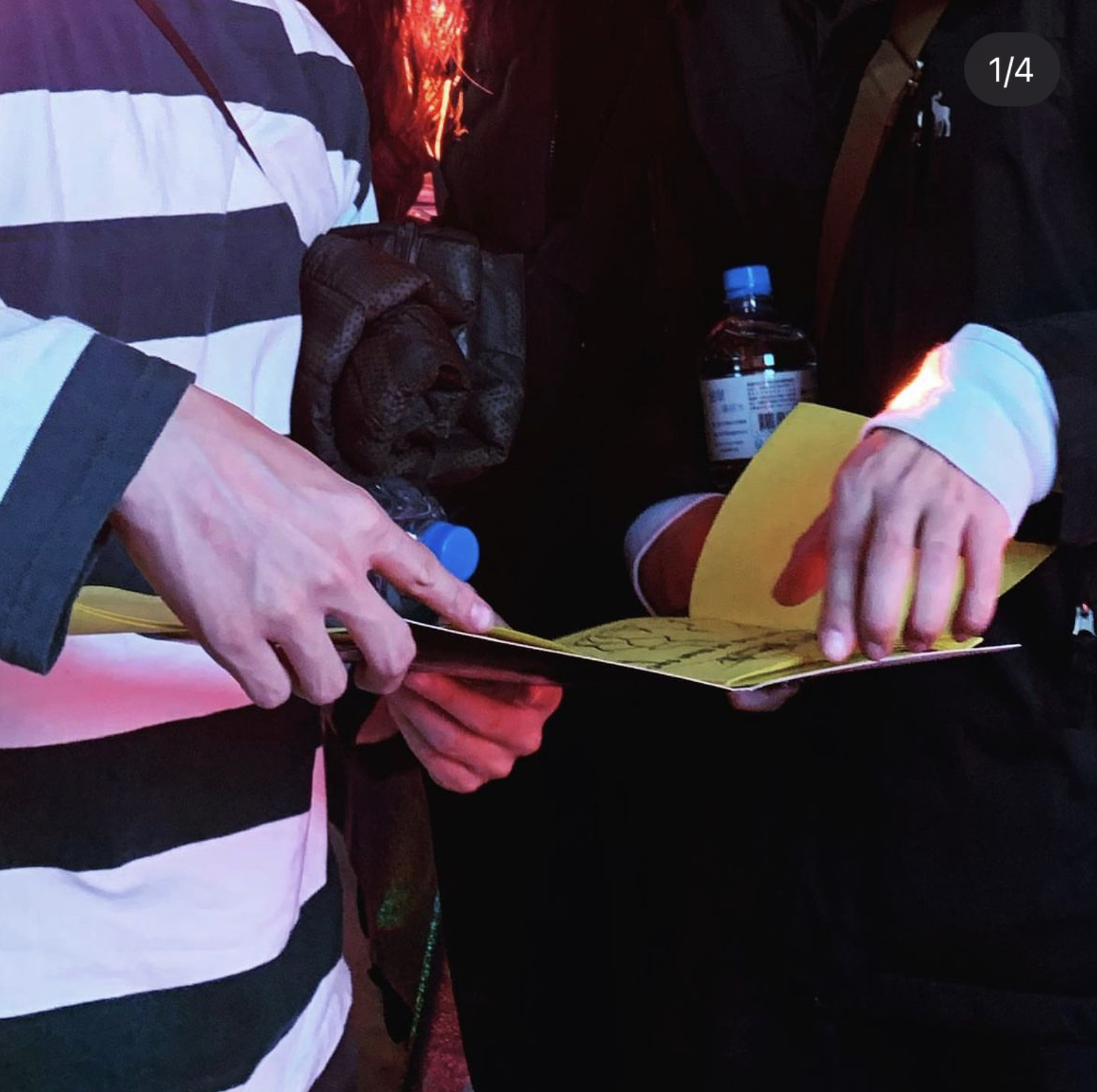

8. My second zine, Mirror 9. Readers flipping my zine together

9. Readers flipping my zine together

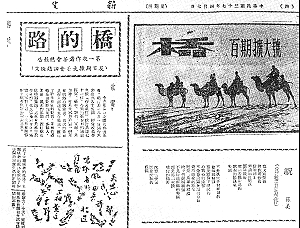

While cultural import from the USIS entered Taiwanese culture, the KMT took over the Taiwan Shin Sheng Daily News in 1945, which the Japanese Colonial Government previously controlled, and became the biggest official newspaper that promoted the series of de-Japanization and re-Sinicization policies. The post-war policies reflected the despising attitude of KMT officials toward the Taiwanese people and local elites, who were excluded from power. The ethnicity crisis, linguistic barriers, and economic inflation the public experienced led to the 228 incident, the most significant uprising later violently suppressed by the KMT government in 1947, bringing the dark era toward the people and the elite class. After the 228 incident, the Taiwan Shin Sheng Daily News started a supplement called Qiao(橋)11, which means “bridge” in mandarin, opening a significant space for forming Taiwanese identity and debating nationality for writers across Taiwan and China. It has been called the Reconstruction of Taiwanese Literature.

At the beginning of 1949, Yang Kui, a prominent writer during the Japanese colonization, drafted A Declaration of Peace urging the newly-arrived KMT government to release all prisoners of conscience and renounce the violent oppression employed during the 228 Incident. Yang sent the self-printed sheet to his friends, and was indirectly reported by the Shanghai newspaper, causing Yang to be subsequently imprisoned on the outlying Green Island for over a decade. In the same year, after the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) established the People’s Republic of China in Beijing, the defeated KMT government retreated to Taiwan. It determined to restrict all civil and political activities that later intensified the mistrust and conflict between the KMT government, inter-ethnic society, and also the education sphere. The April Sixth incident began when police arrested 28 dissident students from National Taiwan University and Taiwan Normal University due to political suspicion of the student association and triggered the most significant clash between police and students in a decade. On 1949 May 19th, KMT launched martial law, starting the so-called White Terror Era.

At the beginning of 1949, Yang Kui, a prominent writer during the Japanese colonization, drafted A Declaration of Peace urging the newly-arrived KMT government to release all prisoners of conscience and renounce the violent oppression employed during the 228 Incident. Yang sent the self-printed sheet to his friends, and was indirectly reported by the Shanghai newspaper, causing Yang to be subsequently imprisoned on the outlying Green Island for over a decade. In the same year, after the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) established the People’s Republic of China in Beijing, the defeated KMT government retreated to Taiwan. It determined to restrict all civil and political activities that later intensified the mistrust and conflict between the KMT government, inter-ethnic society, and also the education sphere. The April Sixth incident began when police arrested 28 dissident students from National Taiwan University and Taiwan Normal University due to political suspicion of the student association and triggered the most significant clash between police and students in a decade. On 1949 May 19th, KMT launched martial law, starting the so-called White Terror Era.

10. World Today magazine No. 511. source: https://soundtraces.tw

![]()

11.Qiao(橋)source: https://www.thinkingtaiwan.com

11.Qiao(橋)source: https://www.thinkingtaiwan.com

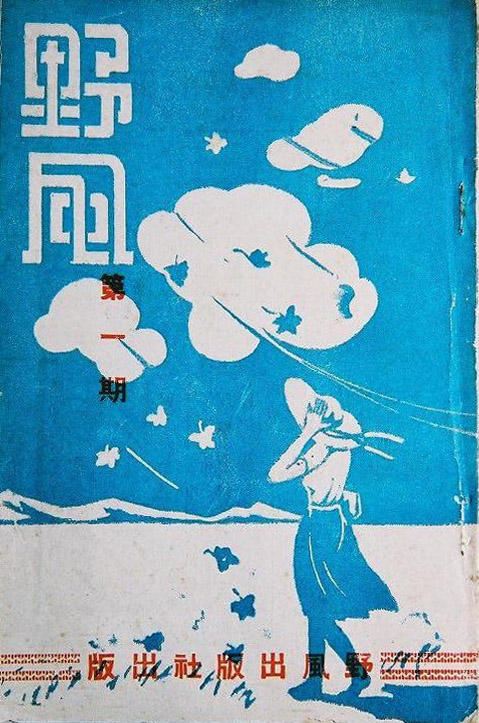

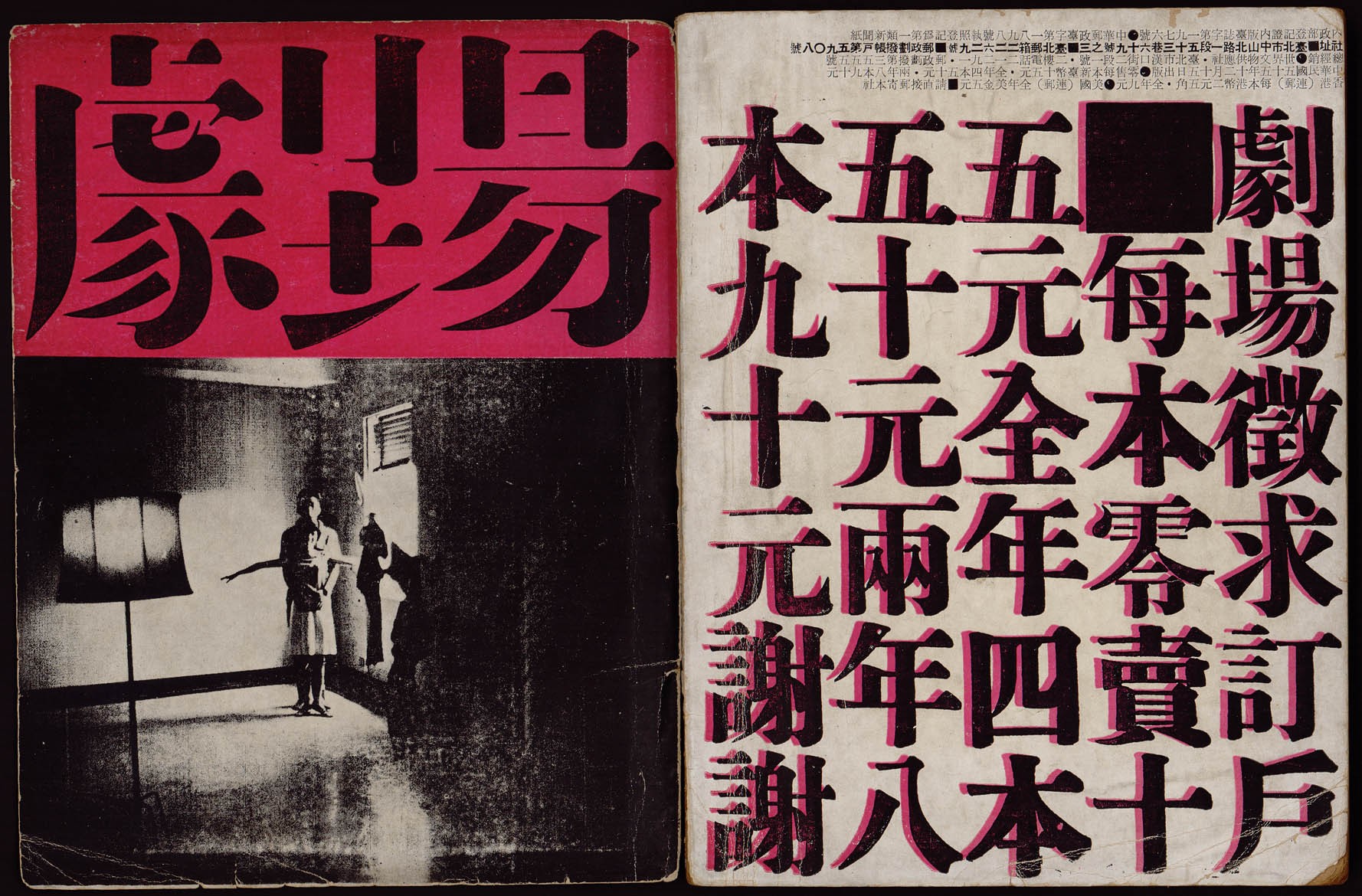

During the White Terror Era (1949-1987), under the strict surveillance toward the publishing authority plus the Anti-Communist policies of the KMT, the authorship of the press and printing techniques were controlled and muzzled by the Printing Act. The content of magazines was generally blasting the Communist and Russian allies. While the creative class were tired of the literature politicization, several employee magazines were published by employees of government enterprises, including Yeh-Fong (Wild Wind) from TSC (Taiwan Sugar Corporation)12 and Shi-Sui (The Gleaners) from Kaohsiung Refinery Plant, and another cultural magazine Wen-Xing (Literature Star)13, was published by the Wen-Xing bookstore. These presses had become informative alternative resources for the public in the 1950s. In the 1960s, young Taiwanese intellectuals started to become aware of Western avant-garde movements through writings and translations, and were eager to align themselves with the innovations of their counterparts in the West. They formed for themselves a concept of what the avant-garde could look like and carried out their own experiments with film and theater. Their little magazines, Jù-Chǎng (Theatre Quarterly)14, played a pivotal role in advocating the latest developments in the Western art world by dedicating more than 90% of its pages to translations of new European and American works.

In 1971, with the People's Republic of China uprising, R.O.C. formally withdrew from the United Nations (U.N.) and broke off diplomatic relations with Japan and the United States. Chiang Ching-Kuo, son of Chiang Kai-shek, assumed the presidency in 1975, followed by a wave of political change called Tang-Wai (outside the K.M.T. party) movement. During the time, the content of magazines was divided; Some focused on literary criticism, such as China Tide and The Intellectual, led by the post-war generation and the young entrepreneur; another was the pro-reformist magazine, such as Taiwan Political Review, led by politicians. Meanwhile, facing the abrupt changes in the political situation and oppression, domestic conflicts and democracy movements happened frequently. Among the chaos, the underground, so-called "illegal" small presses played a significant role in the political sphere.

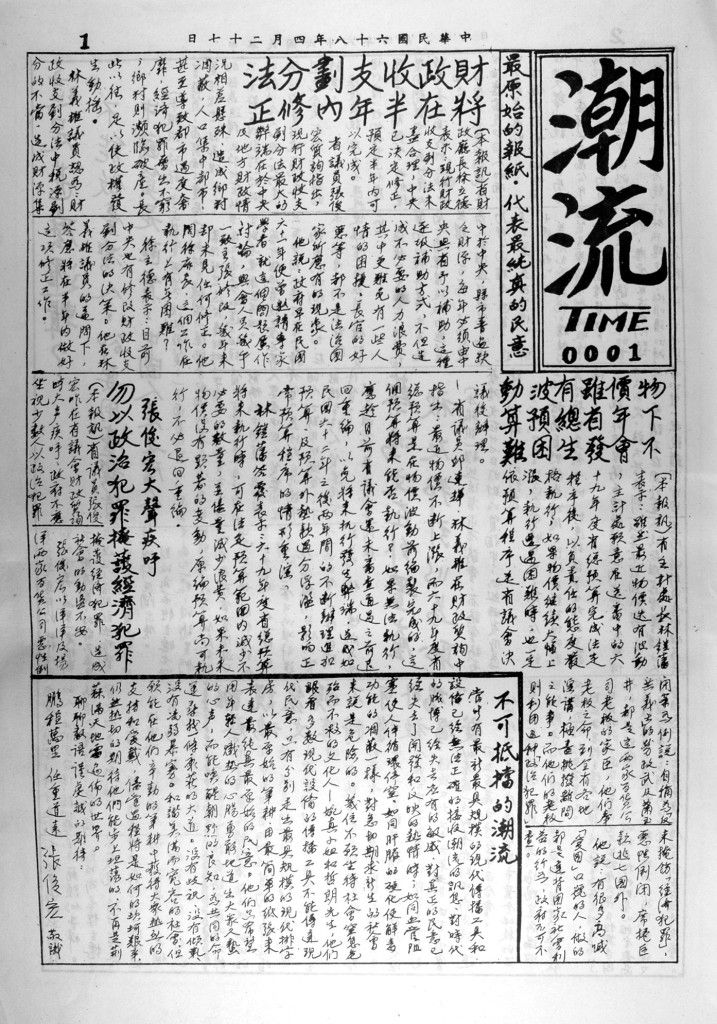

In April of 1979, the journal editor from Taiwan Daily and a reporter from China Times collaborated and published the underground press in Taiwan, the Tide newspaper, which earned the transparency of the Taiwan Provincial Consultative Council. The Cháo Liú (潮流) (Tide) newspaper15 was printed by mimeograph in 9x13 inches and had a circulation of roughly 3000 copies. Though the publishers and the leading printer got arrested in August, Tide had deeply rooted and affected the following blooming of local media and Tang-Wai's movement.

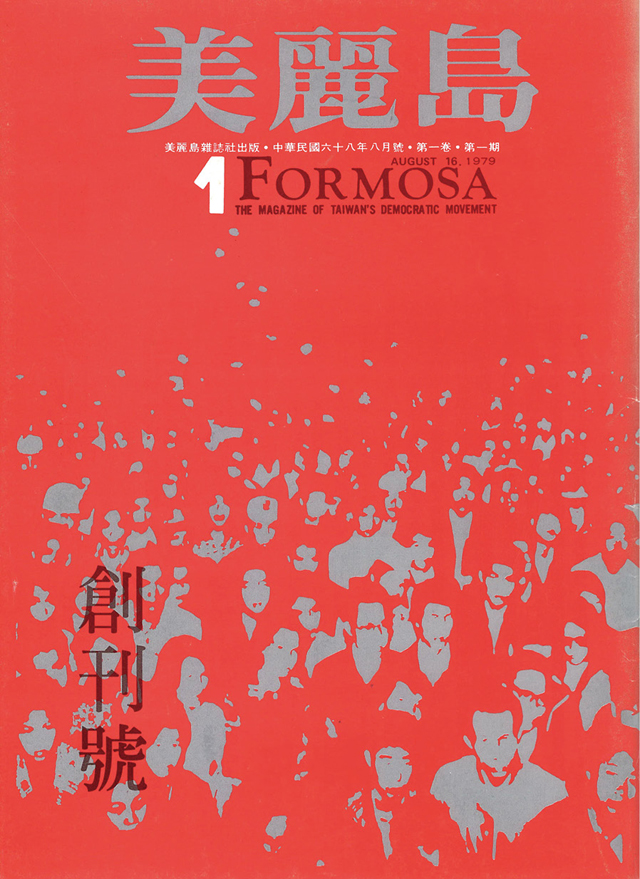

In August 1979, Formosa Magazine16, also known as Mei-li-tao ( 美麗島), was created and organized by Tang-Wai members from different cities and later became the main center of the Tang-Wai movement, with the rising circulation to nearly 140,000 copies. In December 1979, Formosa Magazine held a demonstration commemorating Human Rights Day to promote and demand democracy in Taiwan. Before the demonstration, the military police had already taken up positions and later clashed with the demonstrators. After the incident, all well-known opposition leaders and Tang-Wai members were arrested and held incommunicado for months, during which reports of severe ill-treatment filtered out of the prisons.

Under the suppressed, intense social sphere, the expression and intention of publishers were obscure and carefully hidden under the writing and book covers, such as Birthday Commemoration of Yu's 78-year-old Documentary. The photography book published by the photographer Chen Bo-Wen, who was also involved in the production of the Tide and Formosa Magazine, was the rare record of the Tang-Wai members’ commemoration of the political victim in the Zhongli incident. The book was detained by the authorities within a month of its publication.

Throughout the national turmoil and international situation in the 1970s, Tang-Wai magazines had increased even in risk of revoked detention from the government. According to the statistics for May and June of 1984, KMT banned 22 magazines and three publishers. In other words, one magazine got banned every two days. However, the provocation and the heated backlash toward the repeated political persecution and restricting dictatorship seemed unstoppable. Even though these publications were detained, as long as they registered with new titles, they still had the right to publish. Since 1980, based on the economic growth, the magazines became collectivized and focused on entertainment, economy, technology, and global news. With the influence of the deregulation and international movements, including the third wave of democracy in Asia, the Act Up action, and the pop culture imported from the US, the student resistant networks and movements began to rise. Under the existing censorship, they established their newspaper independently in universities, such as Wild Fire, Transform, Love of Freedom, Raging Billows, East Waves, Equal Sphere, etc. These publications were often followed by student protests and marches that consequently awakened the series of campus restructuring.

In 1971, with the People's Republic of China uprising, R.O.C. formally withdrew from the United Nations (U.N.) and broke off diplomatic relations with Japan and the United States. Chiang Ching-Kuo, son of Chiang Kai-shek, assumed the presidency in 1975, followed by a wave of political change called Tang-Wai (outside the K.M.T. party) movement. During the time, the content of magazines was divided; Some focused on literary criticism, such as China Tide and The Intellectual, led by the post-war generation and the young entrepreneur; another was the pro-reformist magazine, such as Taiwan Political Review, led by politicians. Meanwhile, facing the abrupt changes in the political situation and oppression, domestic conflicts and democracy movements happened frequently. Among the chaos, the underground, so-called "illegal" small presses played a significant role in the political sphere.

In April of 1979, the journal editor from Taiwan Daily and a reporter from China Times collaborated and published the underground press in Taiwan, the Tide newspaper, which earned the transparency of the Taiwan Provincial Consultative Council. The Cháo Liú (潮流) (Tide) newspaper15 was printed by mimeograph in 9x13 inches and had a circulation of roughly 3000 copies. Though the publishers and the leading printer got arrested in August, Tide had deeply rooted and affected the following blooming of local media and Tang-Wai's movement.

In August 1979, Formosa Magazine16, also known as Mei-li-tao ( 美麗島), was created and organized by Tang-Wai members from different cities and later became the main center of the Tang-Wai movement, with the rising circulation to nearly 140,000 copies. In December 1979, Formosa Magazine held a demonstration commemorating Human Rights Day to promote and demand democracy in Taiwan. Before the demonstration, the military police had already taken up positions and later clashed with the demonstrators. After the incident, all well-known opposition leaders and Tang-Wai members were arrested and held incommunicado for months, during which reports of severe ill-treatment filtered out of the prisons.

Under the suppressed, intense social sphere, the expression and intention of publishers were obscure and carefully hidden under the writing and book covers, such as Birthday Commemoration of Yu's 78-year-old Documentary. The photography book published by the photographer Chen Bo-Wen, who was also involved in the production of the Tide and Formosa Magazine, was the rare record of the Tang-Wai members’ commemoration of the political victim in the Zhongli incident. The book was detained by the authorities within a month of its publication.

Throughout the national turmoil and international situation in the 1970s, Tang-Wai magazines had increased even in risk of revoked detention from the government. According to the statistics for May and June of 1984, KMT banned 22 magazines and three publishers. In other words, one magazine got banned every two days. However, the provocation and the heated backlash toward the repeated political persecution and restricting dictatorship seemed unstoppable. Even though these publications were detained, as long as they registered with new titles, they still had the right to publish. Since 1980, based on the economic growth, the magazines became collectivized and focused on entertainment, economy, technology, and global news. With the influence of the deregulation and international movements, including the third wave of democracy in Asia, the Act Up action, and the pop culture imported from the US, the student resistant networks and movements began to rise. Under the existing censorship, they established their newspaper independently in universities, such as Wild Fire, Transform, Love of Freedom, Raging Billows, East Waves, Equal Sphere, etc. These publications were often followed by student protests and marches that consequently awakened the series of campus restructuring.

14. Jù-Chǎng 劇場 source: www.fountain.org.tw

![]() 15. Cháo Liú (潮流) (Tide) newspaper. source: https://www.thinkingtaiwan.com/

15. Cháo Liú (潮流) (Tide) newspaper. source: https://www.thinkingtaiwan.com/

![]()

15. Mei-li-tao (美麗島) newspaper No. 1. source: https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%BE%8E%E9%BA%97%E5%B3%B6%E9%9B%9C%E8%AA%8C

15. Cháo Liú (潮流) (Tide) newspaper. source: https://www.thinkingtaiwan.com/

15. Cháo Liú (潮流) (Tide) newspaper. source: https://www.thinkingtaiwan.com/

15. Mei-li-tao (美麗島) newspaper No. 1. source: https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%BE%8E%E9%BA%97%E5%B3%B6%E9%9B%9C%E8%AA%8C

In 1986, these association members also contributed to the rising community consciousness toward environmental awareness through documenting the Lukang Anti-Dupont Movement16 held by the residents due to the Ministry of Economic Affairs’ permission for the US company DuPont to set up a titanium dioxide plant near Lukang, Changhua County, and later led to the establishment of Environmental Protection Administration in Taiwan. In 1986, DDP (Democratic Progressive Party) was founded, and martial law ended in 1987. The Tang-Wai and student movements not only laid the foundation for the freedom of the press and self-government rights in school but also initiated a new era for zines and subcultures.

In March, 1990, Wild Lily student movement, the first large-scale sit-in demonstration, was initiated by students who sought direct elections of Taiwan's president and vice president and new popular elections for all representatives in the National Assembly. During the demonstration, the inaugurated president, Lee Teng-hui expressed his support of the students' goals and promised full democracy in Taiwan beginning with reforms to be initiated that summer, which would transform Taiwan into a pluralistic democracy. In May, Lee Teng-hui announced the termination of Period of National Mobilization for the Suppression of the Communist Rebellion which had allowed the government to rule with an iron fist for nearly 43 years without following the Constitution and declared: “We will no longer seek to unify China through force,” that bridged a new relationship between two sides. The happening of the Wild Lily student movement and the gradually liberated response of the government not only strengthened the pursuit of Taiwanese democracy in the following decade but also inspired the more open-minded school culture for a new generation of intellectuals.

In March, 1990, Wild Lily student movement, the first large-scale sit-in demonstration, was initiated by students who sought direct elections of Taiwan's president and vice president and new popular elections for all representatives in the National Assembly. During the demonstration, the inaugurated president, Lee Teng-hui expressed his support of the students' goals and promised full democracy in Taiwan beginning with reforms to be initiated that summer, which would transform Taiwan into a pluralistic democracy. In May, Lee Teng-hui announced the termination of Period of National Mobilization for the Suppression of the Communist Rebellion which had allowed the government to rule with an iron fist for nearly 43 years without following the Constitution and declared: “We will no longer seek to unify China through force,” that bridged a new relationship between two sides. The happening of the Wild Lily student movement and the gradually liberated response of the government not only strengthened the pursuit of Taiwanese democracy in the following decade but also inspired the more open-minded school culture for a new generation of intellectuals.

16. Lukang Anti-Dupont Movement. source: https://ourisland.pts.org.tw

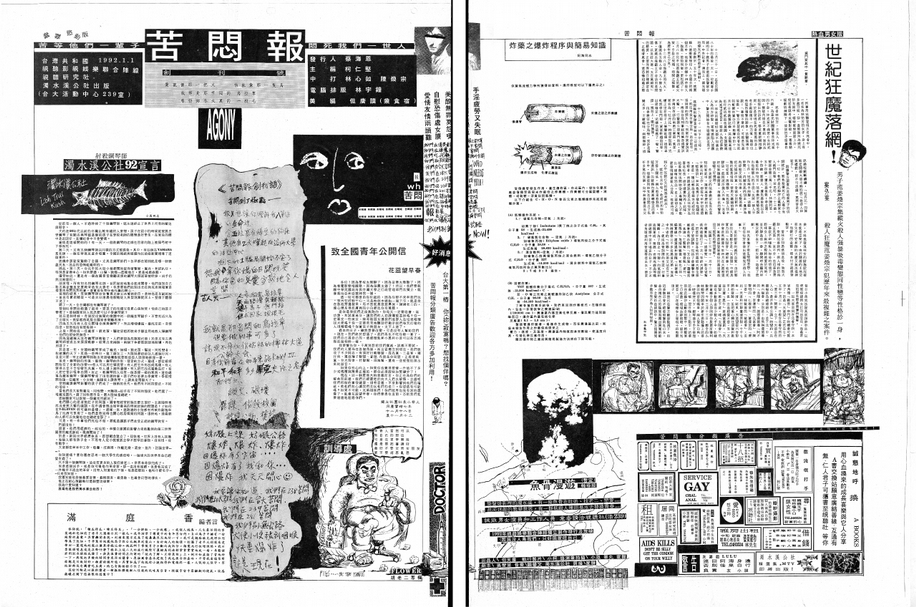

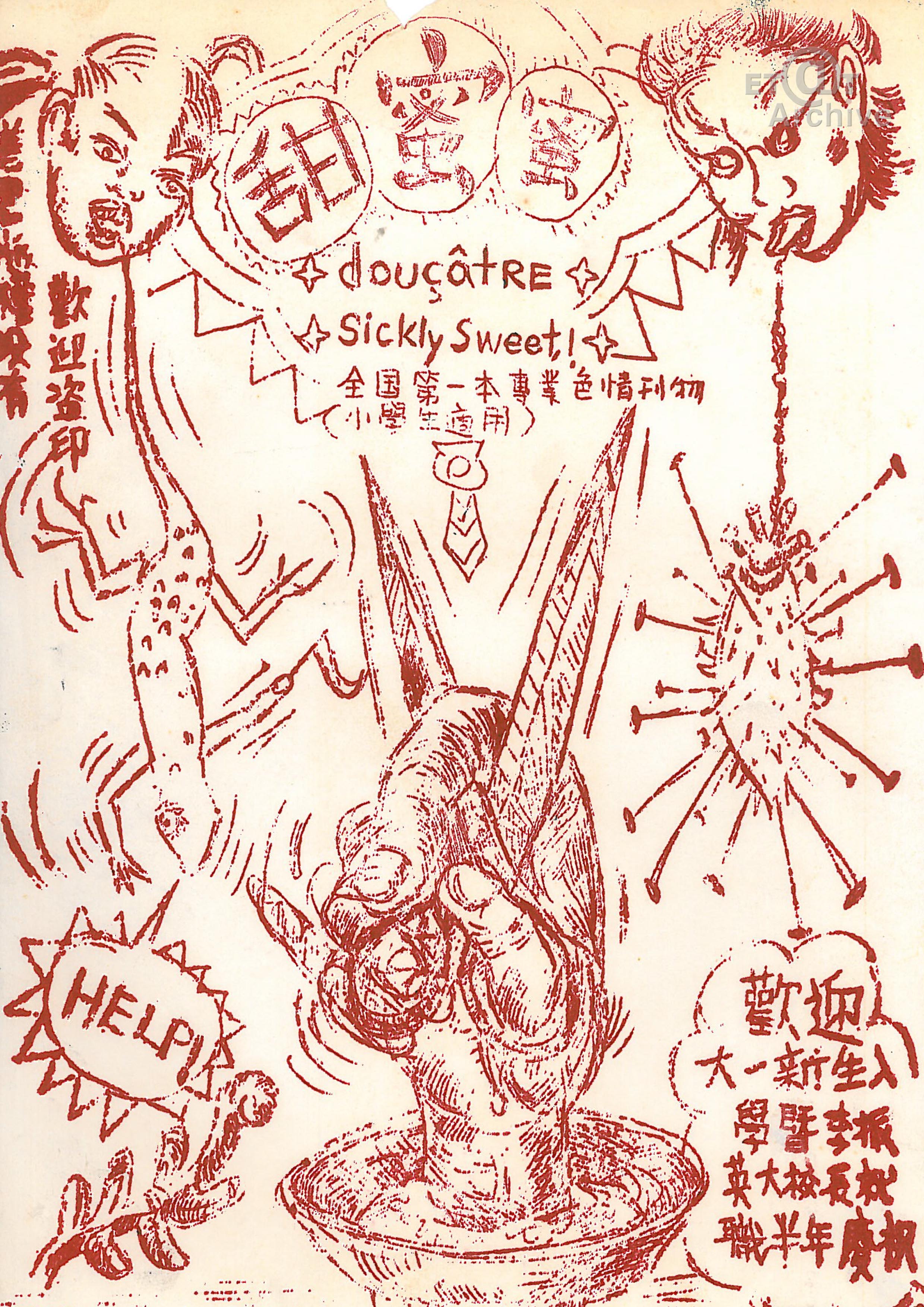

Student publications in 1990, compared to those in the 80s, were no longer restricted by censorship and were deeply inspired by grunge, individualism, and feminism, aided by cable television and the Internet, and were identified as an early form of zine culture in Taiwan. The content of these publications was diverse, ranging from expressing resistance toward credentialism and challenging Confucianism with vulgar culture to the exploration outside of binary politics associated with sexual liberation. Representative publications include kǔ mènbào (苦悶報)(Depression Mag)17, tián mìmì (甜蜜報)(Sickly Sweet)18and Noise, focusing on importing the noise music and vulgar culture; dà biàn bào(大便報)(Poop Mag)19 emphasizes the concept of uncleship.

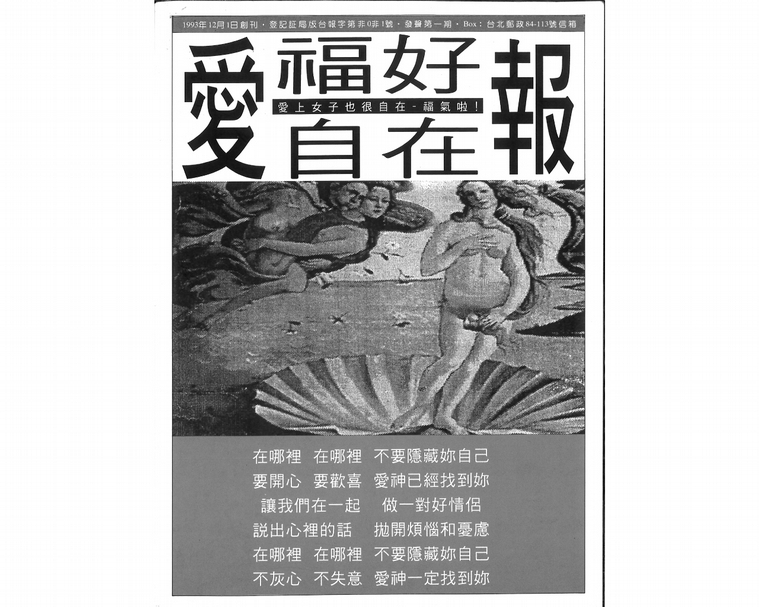

On the other hand, lesbian associations published AIFUHAO Always Mag (愛福好自在報) and Girlfriend, introducing lesbian feminism theories and related history to the gay communities. Another little magazine, Tao-yu pian-yuan(島嶼邊緣)(The Isle Margin), presented Taiwan's cultural hybridity by introducing social ideas in a hyper-connected narrative. Further collaborated with other underground zines, developing their writing style, post-text, by inserting the alternative text (nonsense advertisement, wordplay, intentional misreading) in the main text (western theories, translated literature) to diverge the new meaning and context. In volume no. 10, Tao-yu pian-yuan (The Isle Margin) used “ku-er” as the translation of “queer.” Compared to “queer” in English and American context, ku-er carries the connotation of “cool” and “stylish,” and becomes a floating signifier associated with the vibrant spirit of past queer movements.

On the other hand, lesbian associations published AIFUHAO Always Mag (愛福好自在報) and Girlfriend, introducing lesbian feminism theories and related history to the gay communities. Another little magazine, Tao-yu pian-yuan(島嶼邊緣)(The Isle Margin), presented Taiwan's cultural hybridity by introducing social ideas in a hyper-connected narrative. Further collaborated with other underground zines, developing their writing style, post-text, by inserting the alternative text (nonsense advertisement, wordplay, intentional misreading) in the main text (western theories, translated literature) to diverge the new meaning and context. In volume no. 10, Tao-yu pian-yuan (The Isle Margin) used “ku-er” as the translation of “queer.” Compared to “queer” in English and American context, ku-er carries the connotation of “cool” and “stylish,” and becomes a floating signifier associated with the vibrant spirit of past queer movements.

19. dà biàn bào(大便報) source: https://artouch.com/art-views/review/content-12316.html

![]() 20. AIFUHAO Always Mag (愛福好自在報) source: https://artouch.com/art-views/review/content-12316.html

20. AIFUHAO Always Mag (愛福好自在報) source: https://artouch.com/art-views/review/content-12316.html

![]()

21. Tao-yu pian-yuan(島嶼邊緣)(The Isle Margin) No. 8. source: https://artouch.com/art-views/review/content-12316.html

21. Tao-yu pian-yuan(島嶼邊緣)(The Isle Margin) No. 8. source: https://artouch.com/art-views/review/content-12316.html

04 ︎︎︎ Queer

“In our country, perverses should be everywhere; our country should be a nation of perverse - nation of female, nation of queer, nation of working class, nation of indigenous people, nation of people with disabilities. There will be no community of life without us. Perverse own the country.” - Tao-yu pian-yuan (The Isle Margin)

The context between publication and Taiwanese democracy progress, shows the essential role of publications and zines for self-expression, statement for collective value, and as a way to build communities, and further to challenge the authority. By cross-cultural translation and cross-disciplinary collaborations, the activists and communities are producing the queerness context in Taiwan that not only focuses on the LGBTQI+ community but also connects with post-colonial theory. The activist Chi Ta-Wei defended and analogized lesbian and gay identities along with the absolute subjectivity of Taiwan, by using the English title “Queer Archipelago” to address the geographic contours of Taiwan. He states that ku-er is a cultural hybrid, engaging history writing and ongoing dialogue with queerness abroad. In Taiwanese scholar and writer, Wen Liu’s Non-Western Sexuality, Queer Asia, or Cold War Geopolitics? Repositioning Queer Taiwan in the Temporal Turn, she retraced transnationalism since 2000s in western cultural study, and the Eurocentrism issue that emerged from it and how it extended the research direction of queer theory. Queer transnationalism is particularly focused on the opportunities and problems brought about by the global new paradigm of "queer," "gender," and "LGBT rights," especially the new issues raised by the expansion of "gay and lesbian" identities to the global paradigm under the pretext of human rights, which is reflected in the establishment of many international LGBT organizations in Southern countries since 2000. While the scholars aim to challenge the dominance of Western, Eurocentric perspectives in queer theory, the American queerness becomes the default standards and canon for global queerness to compare with, and the non-western experiences are easily commodified and experienced another layer of essentialization, and queer theory is set as an upper leveled traveling theory22, which can describe diverse subjectivities across regions. Feminist scholar, Arondekar Anjali, and University of Virginia professor, Geeta Patel, pointed out that the power relations between the south and north had not been thoroughly transformed through the transnationalism turn in queer theory, and the importance of area studies was still omitted. Arondekar and Patel further pointed out that the politics of queer and area studies should interweave as isomorphic activities, and affect the contextualization of each other23. In other words, queer studies should open up the temporality and the history in region scale to reconstruct and to break through the linear historical perspective from empires’ colonization.

Wen Liu pointed out that, under the Taiwanese context, queerness is associated with two layers; Firstly, the queerness study should deep dive into the intersectionalities of multiple colonialism and power inequalities within regions, to loosen the binary framework - West to Asia, U.S. to China- from the Cold-War. Secondly, facing the expansion of China's authoritarianism and being situated under the escalating pressure, Queer Taiwan should be allied with communities existing outside of oppressive systems, and incorporate decolonization, as well as subcultures of Sinophone in diaspora, in order to imagine Queer Taiwan as an intersubjectivity - a phenomenal, spontaneous formed collective to share knowledge and provide asylum, when facing warfare, inequality of human rights or suppression of freedom. The heterogeneity in Taiwanese queerness extend the inclusivity and openness toward not only gender and sexuality, but also the right of telling your life, the right for complex personhood, the right of unlearning kinship, the right of reimagine the nation, and finally, back toward the relatedness with others in our everyday lives.

︎︎︎ Read ongoing conclusion in Asterisk as a life form

The context between publication and Taiwanese democracy progress, shows the essential role of publications and zines for self-expression, statement for collective value, and as a way to build communities, and further to challenge the authority. By cross-cultural translation and cross-disciplinary collaborations, the activists and communities are producing the queerness context in Taiwan that not only focuses on the LGBTQI+ community but also connects with post-colonial theory. The activist Chi Ta-Wei defended and analogized lesbian and gay identities along with the absolute subjectivity of Taiwan, by using the English title “Queer Archipelago” to address the geographic contours of Taiwan. He states that ku-er is a cultural hybrid, engaging history writing and ongoing dialogue with queerness abroad. In Taiwanese scholar and writer, Wen Liu’s Non-Western Sexuality, Queer Asia, or Cold War Geopolitics? Repositioning Queer Taiwan in the Temporal Turn, she retraced transnationalism since 2000s in western cultural study, and the Eurocentrism issue that emerged from it and how it extended the research direction of queer theory. Queer transnationalism is particularly focused on the opportunities and problems brought about by the global new paradigm of "queer," "gender," and "LGBT rights," especially the new issues raised by the expansion of "gay and lesbian" identities to the global paradigm under the pretext of human rights, which is reflected in the establishment of many international LGBT organizations in Southern countries since 2000. While the scholars aim to challenge the dominance of Western, Eurocentric perspectives in queer theory, the American queerness becomes the default standards and canon for global queerness to compare with, and the non-western experiences are easily commodified and experienced another layer of essentialization, and queer theory is set as an upper leveled traveling theory22, which can describe diverse subjectivities across regions. Feminist scholar, Arondekar Anjali, and University of Virginia professor, Geeta Patel, pointed out that the power relations between the south and north had not been thoroughly transformed through the transnationalism turn in queer theory, and the importance of area studies was still omitted. Arondekar and Patel further pointed out that the politics of queer and area studies should interweave as isomorphic activities, and affect the contextualization of each other23. In other words, queer studies should open up the temporality and the history in region scale to reconstruct and to break through the linear historical perspective from empires’ colonization.

Wen Liu pointed out that, under the Taiwanese context, queerness is associated with two layers; Firstly, the queerness study should deep dive into the intersectionalities of multiple colonialism and power inequalities within regions, to loosen the binary framework - West to Asia, U.S. to China- from the Cold-War. Secondly, facing the expansion of China's authoritarianism and being situated under the escalating pressure, Queer Taiwan should be allied with communities existing outside of oppressive systems, and incorporate decolonization, as well as subcultures of Sinophone in diaspora, in order to imagine Queer Taiwan as an intersubjectivity - a phenomenal, spontaneous formed collective to share knowledge and provide asylum, when facing warfare, inequality of human rights or suppression of freedom. The heterogeneity in Taiwanese queerness extend the inclusivity and openness toward not only gender and sexuality, but also the right of telling your life, the right for complex personhood, the right of unlearning kinship, the right of reimagine the nation, and finally, back toward the relatedness with others in our everyday lives.

︎︎︎ Read ongoing conclusion in Asterisk as a life form

Perverse Nation Flag from Isle Margin

22. Said, Edward W.. "Traveling Theory Reconsidered". Critical Reconstructions: The Relationship of Fiction and Life, edited by Robert M. Polhemus and Roger B. Henkle, Redwood City: Stanford University Press, 1994, pp. 251-268.

23. Anjali Arondekar, Geeta Patel; Area Impossible: Notes toward an Introduction. GLQ 1 April 2016; 22 (2): 151–171. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-3428687

24. Experient: Space for Footnotes*, is a digital landscape of scenes and historical materials, which I recognize as queerness, including the political graffiti that I scanned from the streets in Tainan, the shouts I’ve recorded from interviewees, and the writing and beliefs written by people. In this interactive digital space, participants can engage with these various forms of media, as well as follow hyperlinks that can teleport them to the further multimedia in the broader contexts. Through Space for Footnotes*, I aimed to create a non-linear browsing experience, that promotes an engagement through the act of wandering with Taiwanese queer history; Space for Footnotes* is similar to Taiwan, an un-nation, unfinished, incomplete but infinitely hybrid.